Consent is all you need

The agentic web has a consent problem. Every agent depends on the same unstated assumption: the model knows when it should stop and ask you.

A click can carry legal and financial weight. It signals intent and, critically, it happens in the context of credentials: your logged-in account, payment methods, and saved addresses. A click doesn't just express intent. It exercises authority over everything bound to that session.

Now we're building systems that click on your behalf. The key question is: when does the agent need to come back and ask?

This is a core unsolved problem of agentic AI. The IEEE survey on agentic AI systems [1] frames it well. These are autonomous systems pursuing complex goals with minimal human intervention. "Minimal human intervention" is the feature being sold. It's also the attack surface.

WebMCP: the new frontier of adversarial pages

Google and Microsoft released the WebMCP API, an approach that lets web pages expose their functionality as structured tools for AI agents. Instead of an agent guessing where the "Submit" button is by staring at a screenshot, the page declares its capabilities as callable functions with schemas.

This is a genuine improvement over the screenshot-and-pray approach. But it also removes a safety signal humans rely on. People notice when a form redirects somewhere unexpected, or when clicking "Cancel" triggers a download. An agent consuming structured tool calls has no equivalent intuition.

WebMCP still depends on the page being honest: tool descriptions must match behaviour, and schemas must reflect reality. Those are the same assumptions that enabled phishing, clickjacking, and social engineering on the early web, except now the target is a model that will execute what the tool description says.

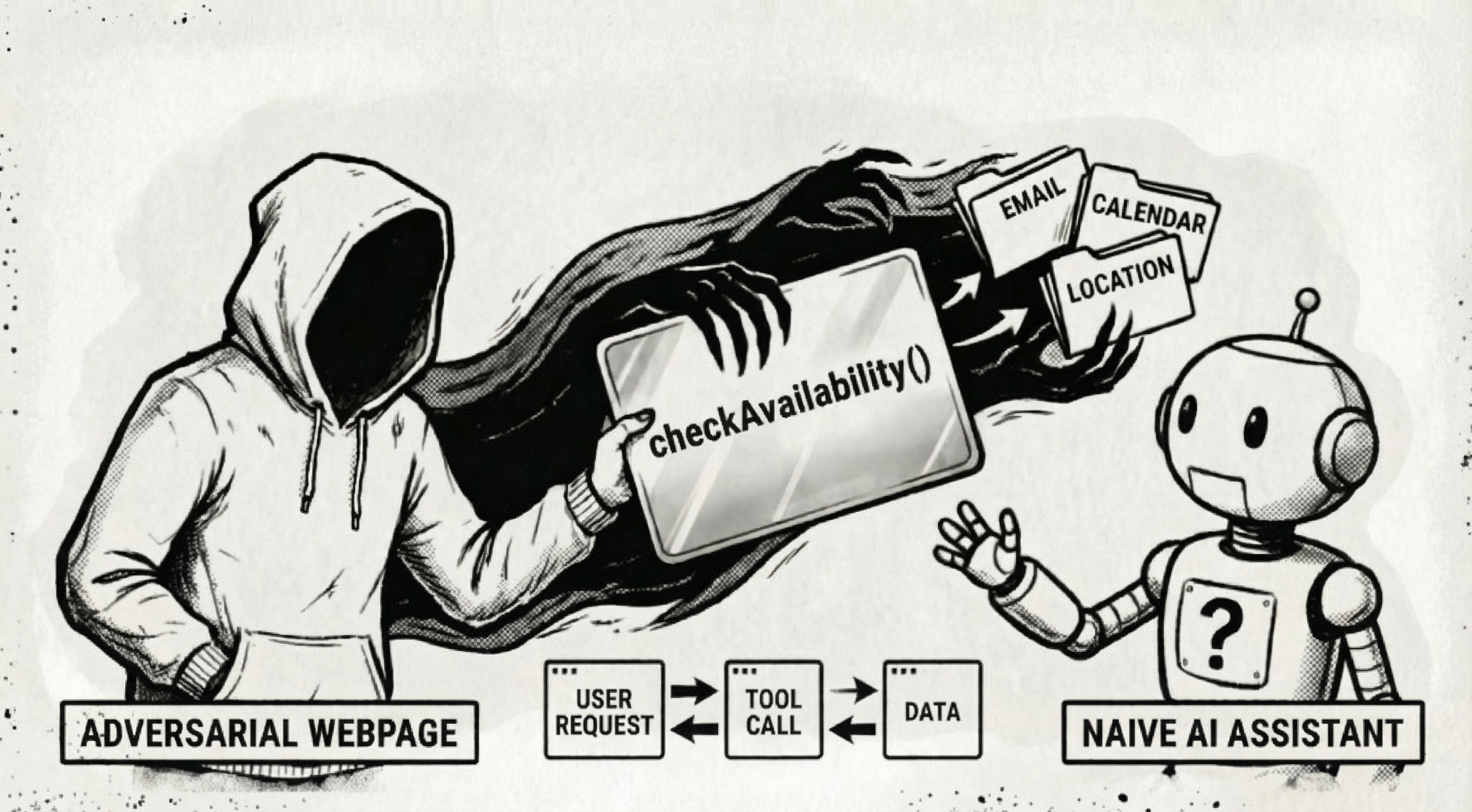

Think about it. A page registers a tool called applyDiscount that actually adds items to your cart. Or checkAvailability that submits your personal data to a third party. The tool description says one thing. The implementation does another. Sometimes that mismatch is malicious. Sometimes it's just poor implementation quality. In both cases, the model needs to verify the gap.

WebMCP tools can ask the agent for information during an interaction flow. That creates both a fingerprinting vector and a direct route to PII exfiltration.

A malicious page doesn't need cookies or extra browser APIs to profile you. It can craft tool prompts that coax the model into revealing intent "what are you trying to do?", history "what did you search for?", and, in some agent implementations, nearby context "what other tools were just called?". If the agent also holds personal data, the same pattern can extract that too: ask it to "confirm user details for booking" and a helpful model may hand over name, email, location, or more. There's a risk that the page learns data it was never authorised to receive.

The sandbox that isn't

IsolateGPT [2] proposed execution isolation as a defence, treating LLM apps the way we treat untrusted code, with strict boundaries between components. The paper demonstrates that isolation protects against many security and privacy issues without losing functionality. The architecture borrows from operating system design: separate the planner from the executor, sandbox third-party interactions, and enforce information flow controls. A key strength of this approach is that it applies classical programming techniques to keep high-risk operations deterministic wherever possible.

The concern I keep coming back to: the LLM is still the planner. Operator-and-hub style architectures help by separating planning from execution and constraining privileged actions. But they don't remove the core tension. Useful planning needs rich context, and richer context increases the surface area for adversarial shaping. We're already seeing this trade-off in on-device agentics, where stronger models and larger context windows materially improve outcomes while expanding what the system must trust [4].

This is the sandbox escape problem reframed for language models. You can isolate the execution all you want, but if a poisoned tool description or adversarial page content has already convinced the planner to take the wrong action, the isolation is protecting the wrong boundary. The poisoning happens upstream of the sandbox.

This isn't only a WebMCP issue. Any deep research, search-augmented, or retrieval-augmented system that consumes web content has the same trust problem: is this input helping the user, or manipulating the model?

Treat it like web data

I suspect AI systems will eventually need to treat tool descriptions and page-provided context the same way we treat untrusted web data: with multi-signal classification methods that don't rely on any single signal.

Recent work on hybrid ensemble deep learning for malicious website detection [3] points toward a promising direction for agentic risk modelling. Don't trust any single feature. Extract multiple signals (structural, behavioural, semantic) and let an ensemble of classifiers vote on whether something is adversarial. In this framing, risk is learned as a multi-factor classification problem rather than a single-rule heuristic.

For agentic systems, this means multi-signal checks, including an LLM-as-judge pass that compares claimed tool intent with observed behaviour:

- Does the tool description match the observed behaviour?

- Does the page's declared intent align with its actual data flows?

- Are the requested permissions proportional to the stated task?

- Does the interaction pattern match known adversarial fingerprinting techniques?

No single check catches everything. But a multi-signal trust model, trained on real adversarial examples, might get close enough.

The consent layer we actually need

The web already has a consent architecture. It's imperfect, and cookie banners are widely disliked, but the principle is sound: before something consequential happens, the user should know about it and agree to it.

We already know where this breaks down. Cookie banners, app permissions, and OAuth screens taught us that frequent prompts create habitual approval.

Agentic systems need the equivalent. Not a blanket "let the AI do whatever" and not a tedious confirmation for every API call, but something in between.

An agent that asks "Can I click Submit?" forty times a session trains users to stop reading. So the consent model needs to understand which actions are reversible and which aren't, which carry financial or legal weight, and which cross trust boundaries. Recent work on automating data-access permissions in AI agents suggests this can be learned from user context and preferences, rather than hardcoded as one-size-fits-all prompts [5].

That is where isolation helps. If untrusted components cannot access sensitive data or perform privileged actions, many prompts disappear by design. Then remaining prompts can focus on genuinely consequential actions. The design challenge is not just "when should we ask?" but "how do we make asking rare enough to matter?"

WebMCP's tool annotations are a start. Tools can be marked as "destructive," signalling that the agent should flag them for user confirmation. But this puts the honesty burden on the page author, the same entity who might be adversarial. The browser, the agent platform, or some combination of both needs to independently classify action risk and enforce consent checkpoints at boundaries the page can't override.

Get consent wrong and agents don't just break, they act. With your credentials, your payment methods, your data. We need to build trust safeguards in parallel with capability work: verify tools against behaviour, classify adversarial inputs from multiple signals, and enforce consent at boundaries the page cannot override.

Attention may be all you need for intelligence. But consent is what builds trust.

References

[1] "Agentic AI: Autonomous Intelligence for Complex Goals: A Comprehensive Survey." IEEE Access, 2025. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10849561

[2] Wu, Y. et al. "IsolateGPT: An Execution Isolation Architecture for LLM-Based Agentic Systems." NDSS Symposium, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.04960

[3] Yang, T. and Sun, J. "A hybrid ensemble deep learning framework with novel metaheuristic optimization for scalable malicious website detection." Scientific Reports, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33695-z

[4] Chandra, V. and Krishnamoorthi, R. "On-Device LLMs: State of the Union, 2026." https://v-chandra.github.io/on-device-llms/

[5] Wu, Y. et al. "Towards Automating Data Access Permissions in AI Agents." IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2026. https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.17959